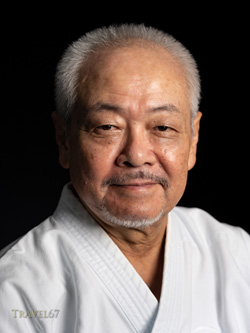

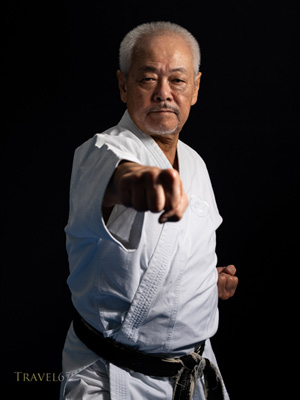

Sensei: Masters of Okinawan Karate #11

Toshihiro Oshiro 9th dan Shima-Ha Shorin-Ryu karate 8th dan Yamanni Chinen Ryu Kobujutsu

21/11/2020

Itoman, Okinawa

My name is Oshiro Toshihiro.

I was born on May 1st 1949 in what is today Nago, Okinawa, in a place known as Haneji Village near Aza. At the age of 16, I moved to Naha City to attend high school. In the second year of high school, I began to practice karate.

When I was younger, around when I was in elementary or middle school, they would have a yearly sports festival in Haneji Village, and there were karate demonstrations. So before the sports festival, the participants would prepare for two three months, either by practicing the kata, or by going up into the mountains to find a piece of wood to make their mura bo (staff). Around 300 people participated in this sport festival. Of course, karate demonstrations were part of the festival. In regards to the karate kata performed at that festival, it was perhaps a kata combining the movements of Nahanchi (Naifanchi) and Pinan kata. In my opinion, that kata was most likely made by either Yabo Kentsu Sensei or perhaps Hanashiro Choumo Sensei.

When I was younger, around when I was in elementary or middle school, they would have a yearly sports festival in Haneji Village, and there were karate demonstrations. So before the sports festival, the participants would prepare for two three months, either by practicing the kata, or by going up into the mountains to find a piece of wood to make their mura bo (staff). Around 300 people participated in this sport festival. Of course, karate demonstrations were part of the festival. In regards to the karate kata performed at that festival, it was perhaps a kata combining the movements of Nahanchi (Naifanchi) and Pinan kata. In my opinion, that kata was most likely made by either Yabo Kentsu Sensei or perhaps Hanashiro Choumo Sensei.

After the Battle of Okinawa, he’d been a POW in Haneji Village. Maybe it was him who created the kata that was performed. I’ve forgotten the kata, but I’m sure if I remembered, it would be interesting to study.

Ever since I was a child, I was deeply interested in martial arts, and since Okinawa was the birthplace of karate, I was drawn to practicing karate.

In my first year of high school, I practiced judo, but in my second year, I went to the karate dojo of Masao Shima Sensei in Kanzatobaru, Naha City. I had just turned 16 at that time. At that particular time, there were only two dojos that practiced Matsubayashi-ryu karate. The honbu (head) dojo under Shoshin Nagamine Sensei and the dojo in Kanzatobaru under Shima Sensei. There were no branch dojos. Of course, under Shima Sensei, training was hard, but Shima Sensei was the head of a company, so he could only be at the dojo once a week. So when he wasn’t there, his senior student would lead practice at the dojo. I loved it. I’d be at the dojo every day of the week.

Of course, wanting to get stronger was perhaps a goal of mine, but for me the biggest interest was the intricacy of using the body, and how it could be used to move efficiently in karate. How can I punch strongly using the body? Or move with power and efficiency? Pursuing the answers fueled my interest karate. I was constantly trying to find those answers, one day when I was 16, I had a revelation. I began to think with clarity on how to use the body more efficiently. The movements of karate done today, have their roots in the past. Of course, my sensei taught me about body movement, and that greatly aided me in understanding. But mainly I was experimenting by myself to better understand body movement. Back in the day, normal people would view those who did karate as violent or ruthless. In the Nagamine Dojo and of course the Shima Dojo, that wasn’t how we conducted ourselves. But the way karate was practiced back then was completely different to now. Of course, practice was strict back then, but it wasn’t with unnecessary violence, also at the time, jiyuu kumite (free sparring) was something strictly forbidden in the dojo. I found out later why it was forbidden. However, before my time, kumite was allowed in the dojo. They had done a lot of kumite at the Honbu Dojo before I entered. The practice in Shima Dojo and Nagamine Dojo wasn’t that different. However, in Matsubayashi-ryu, and perhaps other styles as well, at a dojo they’d teach you a handful  of kata from the system instead of all of them. For example, at Shima Sensei’s dojo, I learned the Pinan kata until Yondan, I practiced Naihanchi Shodan, but didn’t know Naihanchi Nidan or Sandan. I wasn’t taught Pinan Godan. We learned Fukyugata 1 and 2, then the Pinan katas, from there Naihanchi, continuing on to Wankan, Rohai, Passai and Chinto. These were the katas that I learned directly from Shima Sensei. Of course, these were taught to me in great detail by Shima Sensei. When I entered Nagamine Dojo around the age of 16 or 17, I found out there was a Pinan Godan, and Naihanchi Nidan and Sandan. I also learned Ananku, and later Chatan Yara no Kusanku and Gojushiho.

of kata from the system instead of all of them. For example, at Shima Sensei’s dojo, I learned the Pinan kata until Yondan, I practiced Naihanchi Shodan, but didn’t know Naihanchi Nidan or Sandan. I wasn’t taught Pinan Godan. We learned Fukyugata 1 and 2, then the Pinan katas, from there Naihanchi, continuing on to Wankan, Rohai, Passai and Chinto. These were the katas that I learned directly from Shima Sensei. Of course, these were taught to me in great detail by Shima Sensei. When I entered Nagamine Dojo around the age of 16 or 17, I found out there was a Pinan Godan, and Naihanchi Nidan and Sandan. I also learned Ananku, and later Chatan Yara no Kusanku and Gojushiho.

Kobudo was taught at the Nagamine Honbu Dojo. Sai, bo (staff), and tonfa (side-handle baton). I learned the sai and bo. Arround that time, there was a yearly bugeisai (martial arts demonstration festival). It wasn’t exclusively karate, there was jukendo (bayonet fighting), naginata (sword spear), yumi (bow and arrow), and of course karate and kobudo such as bojutsu. I went to see the demonstrations. There was an Okinawan bo practitioner demonstrating a bo kata. I was there watching the demonstration with a college student who studied kendo, we watched the movements, and my friend thought he could outmaneuver and strike. From what I saw, I agreed. Maybe… after looking at the movements of kenjitsu and naginata, the movement of the bo practitioner kind of left me unsatisfied. In Okinawa, bojutsu was practiced extensively from ancient times, and so I thought there hast to be a different way of using the bo. I searched and searched, but I couldn’t find what I was looking for.

Luckily, while I was learning from Shima Sensei, I also was being taught by Kishaba Chokei Sensei. With Kishaba Chokei Sensei, instead a dojo, I went to his home for one-on-one training. I would telephone him and ask when I could practice. By chance, one day I was walking close to his house, so I went to see him. I saw him practicing a bo kata in his garden. I’d been training with him for about ten years, but I’d never seen him even swing a bo. He was practicing Shushi no Kon, Suuji no Kun in the Okinawan language. And at that moment I thought, this is it! I said “Sensei, please teach me.” He was surprised at first, perhaps that I’d found out he practiced bo. For about a week, I learned the sequence of the kata from Chokei Sensei. Sensei said to me, “Oshiro, I’m not a bojutsu specialist.”

“When it comes to bojutsu, the really skilled person is my younger brother, Kishaba Chogi. I’ll personally introduce you to him, so go learn bo from my younger brother Chogi.” I began learning from Kishaba Chogi Sensei, and there I was introduced to Yamanni-ryu bojutsu.

After karate practice, I studied Yamanni-ryu on the veranda of Chogi Sensei’s house. Karate practice would be from around 7.30pm and end at 9.30pm, so it would be pretty late when I went to Chogi Sensei’s house to study bo. A habit of Kishaba Sensei was that first he would always drink two servings of tea, then he would say, “Okay Oshiro-kun, let’s practice on the veranda.” We’d practice well into the night maybe until midnight or 1.00am.

After karate practice, I studied Yamanni-ryu on the veranda of Chogi Sensei’s house. Karate practice would be from around 7.30pm and end at 9.30pm, so it would be pretty late when I went to Chogi Sensei’s house to study bo. A habit of Kishaba Sensei was that first he would always drink two servings of tea, then he would say, “Okay Oshiro-kun, let’s practice on the veranda.” We’d practice well into the night maybe until midnight or 1.00am.

In Okinawa, in the past, training was done differently to now. Chogi Sensei’s wife would often prepare a meal for both Sensei and me. By the time practice finished Sensei’s wife would’ve gone to bed. While we ate, Chogi Sensei would talk to me about karate, kobudo, and stories from his youth. Kishaba Chogi sensei didn’t study Shorin-ryu, but was a Goju-ryu practitioner. He was the direct pupil of Miyagi Chojun Sensei, he learned from Miyagi Chojun Sensei from the age of 14 to 17. So in my chats with Chogi Sensei, he’d tell me about Chojun Miyagi and bojutsu.

In the past, when you studied karate, and it may have been the same for Ryukyu dance, when training finished, you didn’t just go home as you would now, usually you’d sit down with the sensei, maybe Ryukyu dancers didn’t drink, but karateka would have some sake (awamori), and there you’d learn things that weren’t taught in the dojo. For example, the rules of etiquette, where you sit when you enter a person’s home, or how or where you should sit when you enter an unfamiliar place. Before discussion of karate technique, those were the things that were discussed. One of the first things Sensei told me was, “Even if you know karate, when something happens, do not rely on your bare hands, first, look at your surroundings to find a weapon.” That was the first thing he taught me. Later I heard that in many other styles, teachers and students had the same relationship. I think this is less common now. I had a strong desire to go and teach abroad, but I hadn’t had the chance yet.

When I was around 27, Omine Sensei who was senior to me, passed away in the USA. So there was a problem that Omine’s dojo needed a sensei, so I volunteered to go out there. So at 28 years old, I went to America. At the beginning when I came to the United States it was not easy, for example, I would live in the dojo. Omine Sensei had many dojo branches in America at that time. Once a year, all the branch dojos would meet for a training camp in Florida. It was there where I came to an impasse of sorts, Omine Sensei, like Nagamine Sensei, would always do Zen (meditation) in his dojos. The mediation would last around 15 minutes. With me being young at the time, I had a different idea. Instead of sitting and meditating for 15 minutes, wouldn’t it be better to practice basics for 15 minutes? The view on training of the direct students of Omine Sensei was different to mine. It was a problem.

So we had the camp in Panama City, Florida. It was clear that the way I practiced karate was not agreeable with the other students. It is there I thought, this is not a good situation. At that time, I had a good friend who lived in Ohio. One of Omine’s students agreed to take me from Panama City to Ohio by car. The trip took about two days. On the first night of the trip, we stopped at a motel, and I was really wanting a beer, but there was no beer. What! They said we were in a “dry county.” They said in a dry county they don’t serve any alcohol. I was so shocked! But when we went to the county border, all the stores there were liquor stores, all those people from the dry county, would go there to drink. I was really surprised.

So we had the camp in Panama City, Florida. It was clear that the way I practiced karate was not agreeable with the other students. It is there I thought, this is not a good situation. At that time, I had a good friend who lived in Ohio. One of Omine’s students agreed to take me from Panama City to Ohio by car. The trip took about two days. On the first night of the trip, we stopped at a motel, and I was really wanting a beer, but there was no beer. What! They said we were in a “dry county.” They said in a dry county they don’t serve any alcohol. I was so shocked! But when we went to the county border, all the stores there were liquor stores, all those people from the dry county, would go there to drink. I was really surprised.

Once I arrived in Ohio, I stayed at my friend’s place for about two or three months. When I was teaching at the Omine Dojo California, by chance there was a U.S. Marine who I’d taught in Okinawa. He telephoned me in Ohio, and told me he’d found a good place to make a new dojo, and asked me to come back to California. So I returned to California, and my first dojo was located in a place in the Bay Area known as Pacifica. It was really tough. I had no experience running a dojo by myself. At the time I had around 30 to 40 students, but I never had any money. Next to my dojo there was a store that sold fish and chips. I thought “One day, once I have the cash, I’ll buy some fish and chips.” But at that time I was getting by eating one hamburger a day. One day I asked myself “I have 30 to 40 students. So why don’t I have any money?” I realized most students weren’t paying their monthly fees! Later, I asked why they hadn’t paid, and the students said because I hadn’t asked. Ah! Over here, you have to follow up on monthly fees. In Japan, and Okinawa there was no need for that. I realized that running a dojo is tough.

At age 16 and 17, I was studying how to use my body to perform stronger more efficient techniques. I began to be able to move much faster and stronger than before. I was able to hit hard and move fast but I ran into a problem, it was during my test for Shodan (first degree black belt). It was about a year after I first entered the dojo. At that time, you took gradings based on ability, rather than time practiced. So I took my Shodan grading at just over a year. While I was doing the kata during the test, I did kime (tensing / focus) after techniques, but after kime, I couldn’t move on smoothly. This was a shocking revelation for me, and I thought “How can I fix this?” The examiner said “You’re waiting too long between movements.” However, in reality, I wasn’t waiting. I couldn’t move (into the next technique). In budo this is known as itsuki meaning to be stuck in one place. I thougt I must be doing something wrong here. I practiced endlessly, but I could not find a solution.

At the Nagamine Dojo, I learned the intricacies of technique from Nagamine Shoshin Sensei, and also from Nakamura Seigi Sensei and Kushi Jokei Sensei, but the answer of why I couldn’t move was still a mystery to me. It was only after extensive practice of (the bo) Yamanni-ryu with Chogi Kishaba Sensei, that realized how to use the body to avoid being stuck in place. For me personally, Yamanni-ryu has aided my study of karate tremendously. There’s an old saying in Okinawa, that karateka should also study bojutsu. In Okinawa, only bojutsu and karate had been practiced extensively since ancient times. Others such as saijutsu, tonfa and nunchaku, in my opinion, do not have as long a history. The connection between karate and bojutsu is very deep. It was said if an aspect of karate did not make sense, look back to bojutsu for the answer. So bo and karate have this connection. From a practical point of view, before anyone defends themselves with bare hands, it is better to have a weapon at your disposal. In ancient times, bojutsu, kenjutsu or kyujutsu (archery) were the priority. The art of using bare hands as weapons was viewed more as a last resort. It was a method of survival. So even if you were badly wounded you still had a practical means for defense. If one person studied karate for ten years, and another studied the bo for ten years, and another studied the katana (sword) for ten years, those with the weapons would have the advantage. In my opinion there are many shared movements between bojutsu and karate, for example, you can see bojutsu movements in Chatan Yara Kusanku. So from my experience I think that bojutsu existed first then karate came after. The most important aspect of Yamanni-ryu bojutsu is, of course, how one swings and uses the bo, but also the efficient use of the body. When I first started to practice Yamanni-ryu, Chogi Kishaba Sensei would say, “Swing hard, and cut the air. You must always cut the air.”

The idea of kime ist different between karate and bojutsu, especially in Yamanni-ryu, there are not many places in where one stops when studying or practicing Yamanni-ryu.

I remember very important words told by Nagamine Sensei “Readying your gamaku and readying your waist are different.” At the time I thought gamaku and the waist were the same thing so I was perplexed.

When I began learning bo from Kishaba Sensei, when you strike using your right side, you engage your right gamaku. When you finish striking, you engage your left gamaku. Then you engage your left hip or prepare your left hip. If you just prepare your hip, you can’t move. You must immediately, engage your gamaku right to left or vice versa. Doing this keeps you from getting stuck in one place.

When I began learning bo from Kishaba Sensei, when you strike using your right side, you engage your right gamaku. When you finish striking, you engage your left gamaku. Then you engage your left hip or prepare your left hip. If you just prepare your hip, you can’t move. You must immediately, engage your gamaku right to left or vice versa. Doing this keeps you from getting stuck in one place.

When I went to America, I had a lot of questions and theories about stances. Seichusen (center line of the body) and enbusen (line of travel) were concepts in Okinawa, but I hadn’t understood how these concepts were related to karate.

While in America, I studied a book by Nakasone Genwa titled Karate do Taikan. It had photographs of Hanashiro Choumo Sensei and Gushikuma Shinpan Sensei. Gushikuma Shinpan Sensei’s stances blended the traditional and the new. Gushikuma Shinpan Sensei was a school teacher, he taught karate in a physical education format.

Everyone knows Itosu Anko changed karate, but few know or say what he changed. Some say he took the dangerous parts out of the karate. That’s not necessarily the case. Instead karate was changed immensely to fit the school physical education format. But what those changes were no one can explain clearly. If you look at the photos of Gushikuma Shinpan Sensei, his stance is known as shumoku dachi, with his back foot at 90 degrees. In zenkutsu dachi, as used in the Nagamine Dojo, the back foot is at 45 degrees, and you bring the foot straight when moving. Also some Shuri-te styles have foot movement similar to Sanchin dachi. I asked Nagamine Sensei, “Why do we move our feet straight instead of curving?” Sensei answered that it was the old way, the way of old Shuri-te. So now when I looked at the photos of Gushikuma Shinpan Sensei’s shumoku dachi, I had the revelation, that of course if the foot is moving straight, you can’t move smoothly. I finally understood. This brings me back to seichusen (center line of the body).

Nowadays, karate is practiced with the chest pointing directly at the front. Jyun-zuki (stepping punch) is done with the chest forwards. However, Gushikuma Shinpan Sensei’s stances have the chest at 45 degrees. I thought that this was much more practical. One can move quicker, and you can better protect the vulnerable areas. That was when I finally realized what seichusen means for karate. Enbusen isn’t just about where you face when you perform a kata. This revelation came to me after I was in America for about ten years.

I asked Kishaba Chogi Sensei to come to America. When he arrives the first thing he asks me to perform is Sakugawa no Kun. After I finished Sakugawa no Kun he had just one thing to say, “You aren’t moving in a straight line.” That’s when I realized the meaning of enbusen. Enbusen is not just the direction you face to do kata. Enbusen is the opponent themselves. Enbusen represents the opponent’s attacks or movements, the practitioner must move accordingly to the movements of the opponent and react to said attacks accordingly. Enbusen is the opponent. However, the way karate is practiced now is rather puzzling for me, instead of reacting to the opponent’s movements, the practitioner has the opponent in a favorable position from the beginning! In karate, or any budo, you must react to the opponent, the opponent doesn’t just attack from the same spot. For example, in Fukyugata 1, your right leg is forward, then you turn 45 degrees but if you use your right foot as the axis, you’re off-center from your opponent’s attack. So you’re not facing your opponent, or their attack. I thought that is extremely odd from a martial art perspective. I realized I need to move my feet, not use my feet as an axis, and use my seichusen (centerline) as the axis to turn to face the opponent. These ideas are key to Shima Ha Shorin Ryu. With modern karate, many learn to first step then punch, block or kick, but the opponent can move from that place. The punch and the movement must be together. In Shima Ha Shorin Ryu, both the attack and feet move the movement is practically at the same time, but in reality, the hand is slightly faster. It’s vital to have a sense of ukimi. Ukimi is essentially a technique using the body. You create a feeling of there and not there at the same time when you strike. That’s how I understand it.

Karateka from Matsubayashi-ryu dojos, might look and think “Oshiro’s Matsubayashi-ryu is different.”

Karate has spread across the world. This was possible as karate changed into a physical education format. It would be wrong of me to negatively criticize sports karate. So what is the main difference between sport and traditional karate? In sports karate, the movements must be easy to see, so they can be judged in competition. In traditional karate, there’s no judge, movements are minute and hard to discern. You can’t judge them. Now, of course it is fine for people to have different ideas, but some karateka particulary from Europe, they’ve practiced karate for many years, beginning to realize there’s something odd with sports karate.

In Germany I have about 20 branch dojos, many students studied other styles for 20 to 30 years. When they looked at our use of body movement, they switched to study our style.

At a tournament, it is all about what the judge deems correct. So I think it would be good if judges would start to consider real bujutsu and budo. With sport karate anyone can do it. You can all sweat together, you’re all practicing with the same goal, you’re part of a family. This is really valuable. Practical self-defense is rarely the priority, maybe the fourth or fifth reason to train. Number one is social (connection). Everyone can do it, adults and children. This may be the greatest strength of karate, but for example, some just train for tournaments, when they stop competing, they retire from karate. That’s sad. Instead, I believe the study of karate is something that lasts forever.

For me, a good point of doing karate is a deep understanding of my own body. You can’t understand karate without studying Okinawan history. I’m so happy that karate has given me a deeper appreciation of Okinawan history.

Sensei: Masters of Okinawan Karate is a crowd-funded YouTube documentary series about the legendary martial arts teachers of Okinawa, Japan.

Source: YouTube - Sensei: Masters of Okinawan Karate #11 Toshihiro Oshiro

| Interviewer | James Pankiewicz | |

| Videographers | Chris Willson, Michael Olsen | |

| Photographers | Chris Willson, Ralf Smolin | |

| Translations Japanese / English | Kenji Hirai | |

| Video text content extracted |

Ralf Smolin |

|

| Chris Willson Photography | Travel67 | |

| YouTube Serie Masters of Okinawan Karate | Sensei Masters of Okinawan Karate |